After December’s general election defeat, the race to become the new leader of the Labour Party is in full swing.

A key area of debate among the leadership candidates is how to rebuild the ‘red wall’ – seats previously held by Labour in the Midlands and the north of England that fell to the Tories.

Rebecca Long-Bailey got the ball rolling with comments about how Labour should embrace ‘progressive patriotism’ to attract patriotic working-class voters. But the losses suffered in these areas are deeper ingrained and more systemic than many recognise. If Labour want to win back its working-class heartlands, it will need to do far more than raise the Union flag next to the red one.

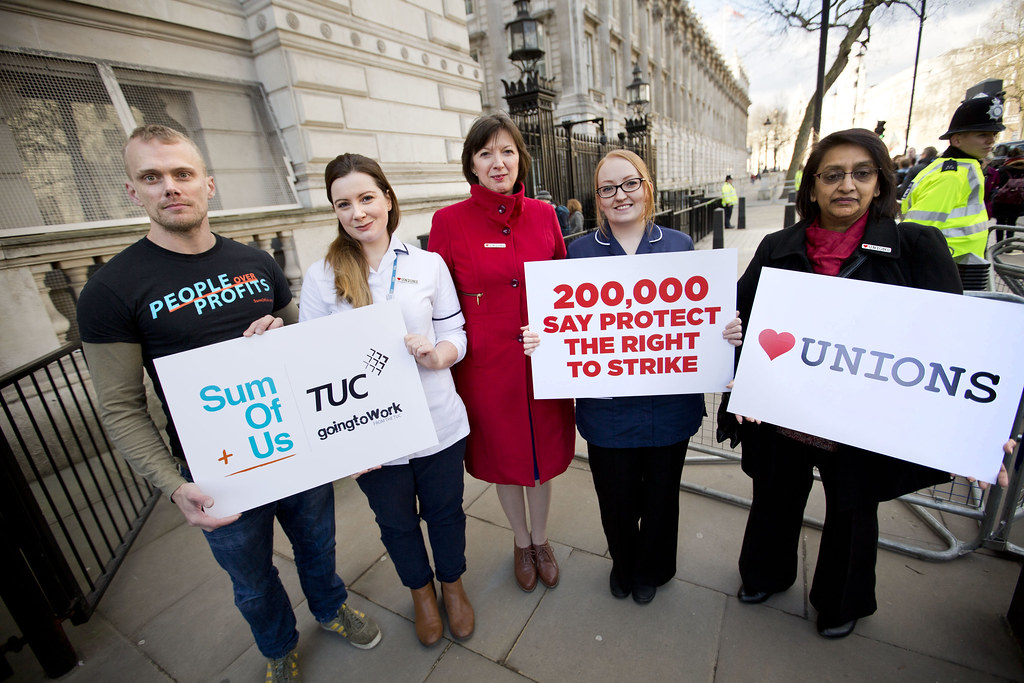

Support for Labour in many parts of the country has been draining for more than a decade, and one significant reason why, along with demographic changes, is the changing nature of the labour movement. The labour movement has always been an alliance between the working class and the progressive middle class. At the founding of our movement was Keir Hardie and Beatrice Webb, but this type of alliance has become strained since the 1980s – with the unions plunging into terminal decline and receiving no real help from Tony Blair when Labour returned to power.

The result is that the labour movement has become ‘gentrified’. The majority of the movement’s standard bearers became middle class progressives due to changes in recruiting grounds, which moved from the workplace and the trade union to the university society.

This change has occurred all over Europe. Take Germany’s SPD: in 1980, 26.5% of their Bundestag members had held formal roles with a trade union, but by 1994 this had reduced by half and has not increased in the two decades since. The opposite is true for SPD parliamentarians who held a formal role with the youth wing of the party (JUSOS), which amounted to 51% in 2017 – up from 13% in the early 1990s.

Labour has experienced similar changes, and this is reflected in its membership which is overly southern and middle class. This problem plagued them during the general election, as the party was able to send hundreds of activists to marginal London constituencies but lacked people power in the Northern heartlands, which ultimately fell to the Tories.

Conscientiously or not, Labour has traded its old working-class heartlands for votes from graduates. This has been an effective switch in some respects, as even in 2019 Labour won the graduate vote by 14 points, but the party was left perilously open to losing heartland voters. Unlike in Europe, where many voters flocked to new populist parties, first past the post may have played a key role in keeping these voters red for some time, until now.

This lack of union influence in working class heartlands has dramatically changed the nature of the labour movement. Suggestions that Labour are no longer the party of the working class are lazy, but it is clear that the party has lost the faith of many of their working-class constituents.

Labour will not win back these voters simply by replacing the Wes Streetings of the party with more Angela Rayners, though there certainly could be a greater showing of working-class involvement in the movement. Instead, Labour’s disconnect can only be fixed in the workplace.

There is clear statistical evidence that unionised workers are far less likely to switch to right wing parties than their non-unionised peers. A study by the University of Reading compared the voting patterns of unionised and non-unionised workers in 16 European nations and concluded that organised workers are less likely to support centre-right parties, and even less likely to support the radical right-wing parties. Radical left-wing parties and social democratic parties benefit equally from organised labour, with workers being less likely to be disturbed by the cultural appeals of the radical right on issues such as immigration. This may explain why union members overwhelmingly supported remaining in the European Union.

There is also appears to be a link between unionisation and turnout in elections. Studies have found that turnout increases with unionisation, especially among lower income constituencies. One US study found that union members were 18% more likely to vote in presidential elections than non-members. Other studies suggest that union members are more politically informed than their non-unionised colleagues.

Overall, there is strong evidence that union membership can be a key factor in helping the left retain voters. Yet this has been neglected by the labour movement.

In Britain, trade union membership has been in decline since the 1980s. But there have been recent signs of a resurgence: union membership increased by 100,000 in the last year. Today unions have just under 7 million fewer members now than they did at their peak in 1978. It is clear that unions need to increase their membership if they are to become more effective organisations.

Unions are not the only de-centralised organisation that can help aid Labour’s electoral chances. A significant part of Lisa Nandy’s leadership pitch centres empowering local democracy which, along with ideas on boosting the co-operative economy, has many merits. In light of the election defeat Labour should be looking beyond Westminster for ideas of how to rebuild the ‘red wall’, because in some areas there is no substitute for organisation

Labour may need a new electoral strategy to win back voters in their heartland areas. But they also cannot continue to neglect other sections of the labour movement that have been so beneficial to working-class voters in the past.

This article was originally published by Open Democracy