Questions about the future of work in Britain are inherently tied to our economic past and present. The era of heavy industry and stable blue-collar jobs collapsed, replaced by highly insecure jobs within the private sector. This decline in quality work has laid the groundwork for a contagious spread of authoritarian populism, that has wreaked havoc on western democracies, while technological advancement means the future, it’s theorised, belongs to automation, with jobs previously done by human hands replaced by AI.

These different threads are entangled in a question that ponders the inevitability of technological determinism and asks whether work is something that provides value and pride or is something to be liberated from. Labour MP Jon Cruddas dutifully provides an answer in his new book The Dignity of Labour.

The dignity of work is often an afterthought in the discussions around jobs in Britain today. Cruddas outlines how, in a time before Thatcher, jobs connected a family together while providing a sense of social connection and value. This was lost as the UK moved towards a knowledge-based economy.

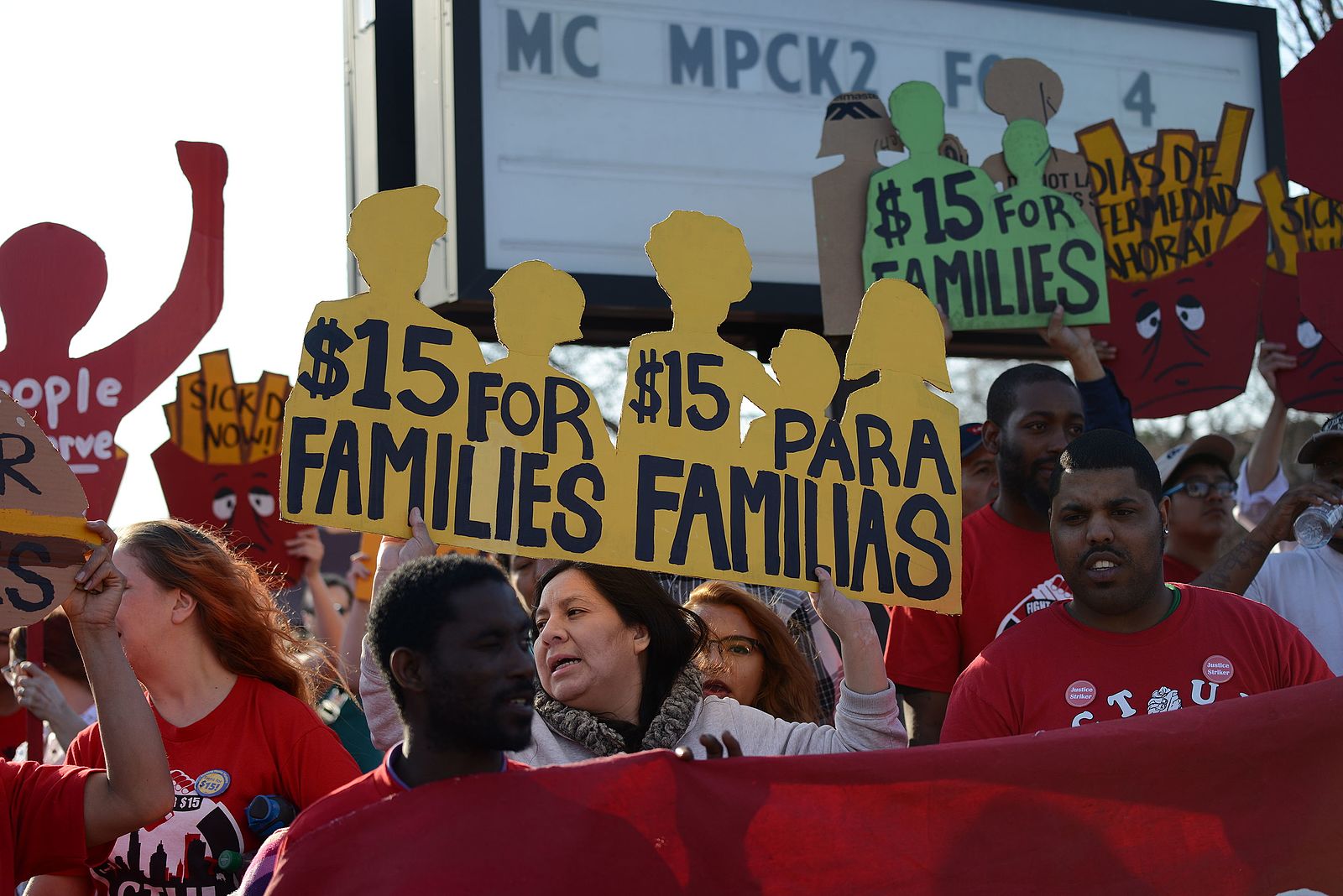

This shift meant the skills and value of the working-class declined sharply, with previously solid industrial jobs replaced by exhausting, degrading and insecure work. Work that offers neither financial security, dignity, personal happiness or even the possibility of a good diet.

As industry abandoned parts of the country, Amazon warehouses and others swept in to exploit, yet no one looking in paid much notice. Before Brexit, many former industrial towns and coastal communities seldom received any attention which explains why, following the EU Referendum, there was a rush to dismiss them as ignorant xenophobes without understanding the deep discomfort that prompted these communities to opt for a radical change.

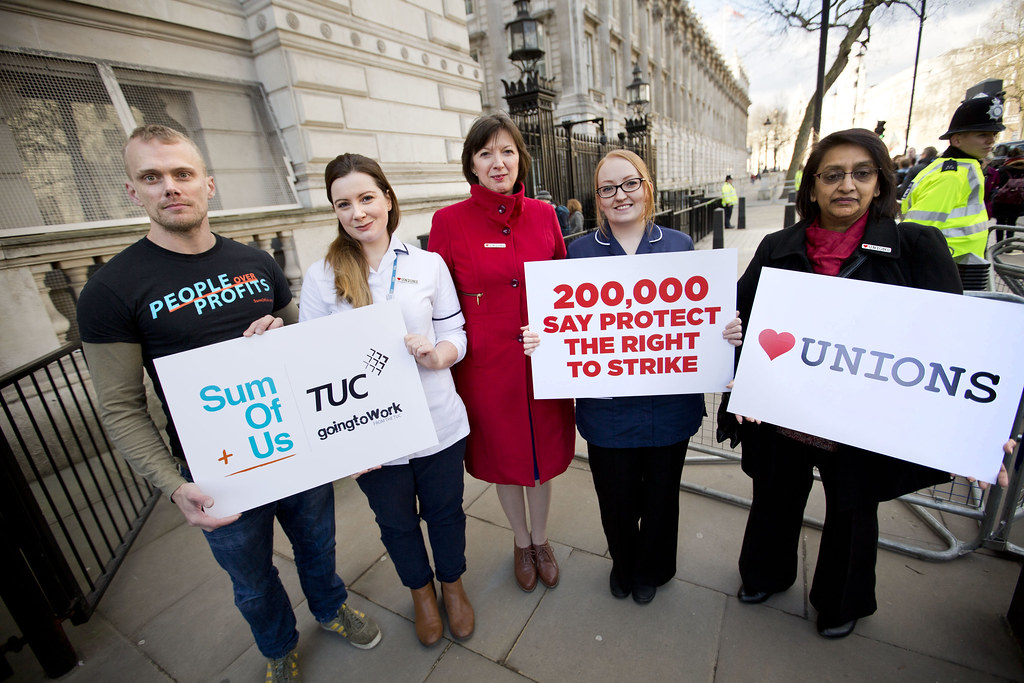

Cruddas highlights that work, and the type of work can create a community. The two are symbiotic, embedded in the supplementing of the other. When the industries were dominant, it created a strong sense of social solidarity underpinned by the powerful trade unions. Unsurprising, that in the era of social fragmentation and atomisation, the unions are weak and as a result, the jobs are insecure.

However, Cruddas doesn’t just blame Thatcher and deindustrialisation for this decline. New Labour isn’t spared in the criticisms of this degeneration of British society. He laments New Labour’s encouragement of a knowledge-based economy in which blue-collar skills were devalued and made redundant, thus witnessing the demise of British car plants.

A particular example that Cruddas, perhaps unsurprisingly, traces is the closure of Ford car productions in Dagenham in 2000. In general, he reflects upon how New Labour themselves shifted the party away from class politics by unreservedly embracing globalisation and all that it entailed. The decline of union power, central to the fragmentation of class politics, was unchallenged by New Labour with new statist ideas coming to replace a longstanding trust in the union movement to deliver material benefits.

In what is a demonstration of his old leftist views, Cruddas viewed tax credits as “funded by a growth engineered through an alliance with finance capital” that replaced collective bargaining.

Most fascinatingly, Cruddas objects to the leftist embrace of automation and what it entails for the future. There is a recent movement within left-wing spaces that envisions the possibilities of where work belongs to robots. This includes a clamour for UBI, Universal Basic Income, and envisaging a society where people are no longer tied to work but emancipated to pursue creative endeavours.

He takes issue with Paul Mason’s belief that automation breaks the link between labour and value triggering a transition from capitalism. For Cruddas, postcapitalist Marxists of the modern era are markedly different in how they embrace the removal of materialism from labour.

He asks whether it would be in their logical interests to resist the employment effects of the pandemic or protest to defend work that is gradually disappearing. Tellingly, Cruddas sees a disconnect between the philosophy of these modern Marxists and the ethical socialism of a trade union culture as the latter still sees value in physical human labour.

Here, Cruddas is wonderfully thoughtful and nuanced. He cited a BBC event in 2017 in Dagenham where people in the community were probed for their thoughts on a number of issues including UBI, individual rights, precarious work and union recognition.

What Cruddas established was that work could provide hope but it could also offer humiliation. It had the capacity to entirely atomise social relations and networks but also forge a community and sense of solidarity out of them. People wanted meaningful work, and not what he referred to as degrading “bullshit jobs”. Whereas the postcapitalist Marxists are very simplistic in their view of a work-absent future, Cruddas explores in detail and nuance the intrinsic value of labour that has been embedded into societies since the dawn of time articulating how work can provide a sense of identity, belonging and security, yet also be utterly exhausting, damaging and degrading for the physical, mental and emotional health.

Cruddas’ book offers a glimpse into the scale of the social trauma for many communities that relied on industrial jobs for a sense of security and belonging and were faced with a reality where these jobs no longer existed.

Fully automated communism is essentially accepting this reality, regarding the possibility of deepening unemployment as automation accelerates, by trying to put on a brave face. And though Cruddas disputes the premise that the future will be without work entirely, he also rejects the idea that automation should be regarded as a natural process.

Cruddas also mentions populism and dissatisfaction with liberal democracy in his book. Removing work from the theatre of politics and leaving it to the market has left many of these communities to feel as though the world has changed to their detriment.

Authoritarian populists such as Donald Trump appeal to this, pitching an idea that liberal democracy has failed the working people in favour of prioritising a liberal professional class. The world was better before and must go back to that. Cruddas’ book articulates how the severe degradation of work can wither away communities and create feelings ripe for being exploited by populists and nationalists.

A key reason for this is what the concept of the nation today means in a globalised world where attachments to national communities aren’t as significant as they were before. Cruddas explains that the modern-day left struggles with conversations on this but maintains that those who feel themselves to be citizens of anywhere as opposed to somewhere, are not the only people who should be included in this conversation, nor do they even constitute a majority of what the British public think.

This is a familiar conversation on the left that surfaces in the aftermath of whatever appalling result that has just taken place for the Labour Party. Cruddas is correct in his assertion that the appeal of nationhood cannot be ignored. Indeed, English nationalism is a strong element in why the Tories have recently been so dominant, and the underpinning identity of most Leave voters in the country.

The book is a fascinating read and at the end of it, one might be left wondering in bemusement as to why Cruddas is merely a peripheral backbencher in the mechanisms of the Labour Party. Cruddas stems from a strand of the old communitarian left that drew a symbiotic link between work and community. His book presents an argument for these values still having a place today.